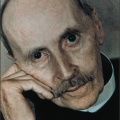

Romain Rolland, (born Jan. 29, 1866, Clamecy, France – died Dec. 30, 1944, Vézelay), French novelist, dramatist, and essayist, an idealist who was deeply involved with pacifism, the fight against fascism, the search for world peace, and the analysis of artistic genius. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915.

Romain Rolland, (born Jan. 29, 1866, Clamecy, France – died Dec. 30, 1944, Vézelay), French novelist, dramatist, and essayist, an idealist who was deeply involved with pacifism, the fight against fascism, the search for world peace, and the analysis of artistic genius. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915.

At age 14, Rolland went to Paris to study and found a society in spiritual disarray. He was admitted to the École Normale Supérieure, lost his religious faith, discovered the writings of Benedict de Spinoza and Leo Tolstoy, and developed a passion for music. He studied history (1889) and received a doctorate in art (1895), after which he went on a two-year mission to Italy at the École Française de Rome. At first, Rolland wrote plays but was unsuccessful in his attempts to reach a vast audience and to rekindle “the heroism and the faith of the nation.” He collected his plays in two cycles: Les Tragédies de la foi (1913; “The Tragedies of Faith”), which contains Aërt (1898), and Le Théâtre de la révolution (1904), which includes a presentation of the Dreyfus Affair, Les Loups (1898; The Wolves), and Danton (1900).

In 1912, after a brief career in teaching art and musicology, he resigned to devote all his time to writing. He collaborated with Charles Péguy in the journal Les Cahiers de la Quinzaine, where he first published his best-known novel, Jean-Christophe, 10 vol. (1904–12). For this and for his pamphlet Au-dessus de la mêlée (1915; “Above the Battle”), a call for France and Germany to respect truth and humanity throughout their struggle in World War I, he was awarded the Nobel Prize. His thought was the centre of a violent controversy and was not fully understood until 1952 with the posthumous publication of his “Journal of the War Years, 1914–1919”. In 1914 he moved to Switzerland, where he lived until his return to France in 1937.

Rolland’s masterpiece, Jean-Christophe, is one of the longest great novels ever written and is a prime example of the roman fleuve (“novel cycle”) in France. An epic in construction and style, rich in poetic feeling, it presents the successive crises confronting a creative genius – here a musical composer of German birth, Jean-Christophe Krafft, modeled half after Beethoven and half after Rolland – who, despite discouragement and the stresses of his own turbulent personality, is inspired by love of life. The friendship between this young German and a young Frenchman symbolizes the “harmony of opposites” that Rolland believed could eventually be established between nations throughout the world.

After a burlesque fantasy, Colas Breugnon (1919), Rolland published a second novel cycle, L’Âme-enchantée, 7 vol. (1922–33), in which he exposed the cruel effects of political sectarianism. In the 1920s he turned to Asia, especially India, seeking to interpret its mystical philosophy to the West in such works as Mahatma Gandhi (1924). Rolland’s vast correspondence with such figures as Albert Schweitzer, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, and Rabindranath Tagore was published in the Cahiers Romain Rolland (1948). His posthumously published Mémoires (1956) and private journals bear witness to the exceptional integrity of a writer dominated by the love of mankind.

Nazira Artykbayeva, librarian of the International Book Department